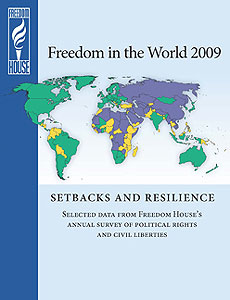

Organizația de monitorizare a drepturilor omului Freedom House a dat publicității raportul său pe 2009 despre evoluția libertății în lume în 2008. Organizația acordă note de la 1 – 7 (1 cel mai liber). În acest clasament figurează și România și Republica Moldova.

ROMÂNIA

Political Rights Score: 2

Civil Liberties Score: 2

Status: Free

Overview

After joining the European Union (EU) in January 2007, Romania was thrown into political turmoil in April when the prime minister fired cabinet ministers backed by President Traian Basescu and narrowed the ruling minority coalition. Parliament suspended Basescu that month, but he was reinstated after easily winning a May referendum on his removal. Meanwhile, the EU warned in June that Romania could face sanctions in 2008 if it failed to make progress on judicial reforms and anticorruption efforts.

——————————————————————————–

In late 1989, longtime dictator Nicolae Ceaucescu was overthrown and executed by disgruntled Communists. A provisional government was formed under Ion Iliescu, a high-ranking Communist, and elections soon followed. Iliescu lost power in 1996 elections but reclaimed the presidency in 2000; the former Communist Party, renamed the Party of Social Democracy (PSD), took power in that year’s parliamentary elections, with Adrian Nastase as prime minister.

In 2004, Traian Basescu of the Alliance for Truth and Justice (comprising the National Liberal Party and the Democratic Party) defeated Nastase in a presidential runoff. The PSD secured a plurality of seats in Parliament, but Basescu’s presidential victory led to a majority coalition between the Alliance for Truth and Justice, the Humanist Party (which subsequently changed its name to the Conservative Party, or PC), and the Democratic Union of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR). Calin Popescu Tariceanu of the National Liberal Party (PNL) became prime minister.

The ruling coalition proved rather unstable. The PNL and the Democratic Party (PD)—which Basescu formally left to become president—clashed over the presence of Romanian troops in Iraq, constitutional reform, control of the security forces, and the holding of early elections. In December 2006, the PC withdrew from the coalition, and a rebel PNL faction led by Theodor Stolojan reorganized as the Liberal Democratic Party (PLD), which sided more often with the PD.

In order to fulfill European Union (EU) accession requirements in 2006, the government made a notable effort to speed up judiciary reform and eradicate corruption. The country joined the EU as scheduled on January 1, 2007. After accession, however, the friction between the president and prime minister quickly flared into direct confrontation, with the PSD exploiting the rift and lending tactical support to Tariceanu. Much of the disagreement appeared to stem from the president’s aggressive pursuit of the EU-backed reforms, which his opponents accused him of politicizing.

On April 1, Tariceanu fired eight ministers supported by the president and PD, ousting the latter from the ruling coalition. The remaining two coalition members, the PNL and UDMR, held just 109 seats in the 469-seat bicameral Parliament. At the PSD’s urging, Parliament on April 19 voted, 322 to 108, to suspend Basescu and organize a referendum on his removal. The lawmakers, including the PNL, accused him of exceeding his constitutional authority by meddling in the cabinet, influencing anticorruption prosecutors, and using the intelligence services against his political enemies. They proceeded with the referendum despite a nonbinding Constitutional Court finding that Basescu had not broken the law. In the May 19 poll, 74 percent of participating voters rejected impeachment, with a turnout of 44 percent.

The European Commission welcomed the result, urging the Romanian leadership to work together and continue with its stalled reform agenda. In a June report, the commission warned that Romania would face sanctions if it failed to make progress on corruption and judicial reforms within a year. Another EU warning in October, threatening to withhold a quarter of the country’s 2008 agricultural aid, was rescinded in December after the government improved its oversight of how the money was distributed to farmers.

Notwithstanding the EU warnings, the two sides seemed locked in a political stalemate for much of the year. The president lacked the authority to call elections or fire ministers, and his opponents appeared unwilling to face voters given their low popularity. Tariceanu’s minority government narrowly survived a no-confidence vote in early October, and his PNL won just 13 percent of the vote—behind the PD’s 29 percent and the PSD’s 23 percent—in European Parliament elections in November, though voter turnout was less than 30 percent. The PLD, which captured 8 percent, announced plans to merge with the PD the following month.

Political Rights and Civil Liberties

Romania is an electoral democracy. Elections since 1991 have been considered generally free and fair. The directly elected president does not have substantial powers beyond foreign policy. He appoints the prime minister, who remains the most powerful politician, with the approval of Parliament. The members of the bicameral Parliament, consisting of the 137-seat Senate and 332-seat Chamber of Deputies, are elected for four-year terms, and a 2004 constitutional amendment stipulates that the president is now elected for a five-year term. A 5 percent electoral threshold for representation in Parliament favors larger parties; six parties won representation in the last elections. The president is not permitted to be a member of a political party.

The constitution allots a seat to each national minority that passes a special threshold lower than the 5 percent otherwise needed to enter Parliament. In the 2004 elections, 18 such seats were allotted. While the ethnic Hungarian minority is represented in the ruling coalition, political participation and representation of Roma is very weak.

Romania significantly stepped up its anticorruption efforts ahead of EU accession. In 2006, anticorruption agencies were reorganized and granted greater authority to investigate corruption at the highest levels, including in Parliament. The quantity and quality of high-level corruption probes increased significantly, and a number of officials, judges, and police officers were arrested and convicted. However, the June 2007 EU progress report noted a pattern of weak or suspended sentences in high-level corruption cases, blunting the effects of the stepped-up prosecutions. In July 2006, the government approved legislation to establish a National Agency for Integrity, tasked with vetting public officials’ assets. It began operations in December 2007, but its future was uncertain after one of its chief proponents, Justice Minister Monica Macovei, was dismissed by the prime minister in April. In October, Agriculture Minister Decebal Traian Remes resigned after being caught on video arranging a bribe, and Macovei’s replacement as justice minister, Tudor Chiuariu, resigned in December after allegedly abusing his position in a real estate deal. Romania was ranked 69 out of 180 countries surveyed in Transparency International’s 2007 Corruption Perceptions Index, the worst ranking in the EU.

The constitution enshrines freedom of expression and the press, and the media are characterized by considerable pluralism. Government respect for media freedoms had been increasing in recent years. However, in January 2007, the Constitutional Court struck down reforms that had decriminalized libel and defamation, effectively reinstating them in the penal code. President Traian Basescu drew criticism in May for seizing the mobile telephone of a reporter who tried to interview him while he was grocery shopping on the day of the impeachment referendum. In September, Parliament appointed a former PSD official to head the public television broadcast station, raising concerns about political bias. The government does not restrict access to the internet.

Religious freedom is generally respected, although “nontraditional” religious organizations encounter difficulties in registering with the state. The government formally recognizes 18 religious groups, each of which is eligible for some state support. The Romanian Orthodox Church remains dominant. In December 2006, Parliament passed a law requiring all religions to have a membership equal to at least 0.1 percent of the population in order to be officially acknowledged. Moreover, nontraditional religions must undergo a 12-year “waiting period” prior to recognition. The government does not restrict academic freedom.

The constitution guarantees freedom of assembly and association, and the government respects these rights in practice. The Romanian civil society sector is vibrant and able to influence public policy, increasingly by working through EU officials and mechanisms. Workers have the right to form unions and strike, but in practice many employers work against unions, and illegal antiunion activity is rarely punished.

The judiciary is one of the most problematic institutions in Romania, though a number of important reforms were passed in 2006, ahead of EU accession. The justice budget was increased, and the court infrastructure was renovated. Improvements were made to the recruitment, training, promotion, and disciplinary systems for judges and clerks, but the June 2007 EU report said further efforts were needed in this area. The government and Parliament’s ongoing review of the civil and criminal codes was hampered by political clashes in 2007.

A June 2007 Council of Europe report, citing anonymous sources, reiterated earlier allegations that Romania had hosted a secret CIA facility where terrorism suspects were abused and interrogated between 2003 and 2005. Romanian leaders restated their denial of the claims. Conditions in ordinary prisons remain poor.

Romania’s 18 recognized ethnic minorities have the right to use their native tongue with authorities in areas where they represent at least a fifth of the population, but the rule is not always enforced. Discrimination against Roma continues, especially in housing, access to social services, and employment. Basescu was criticized for at least two well-publicized ethnic slurs in 2007, but in October he became the first Romanian government official to formally apologize for the Holocaust-related deportation of Roma during World War II. People with disabilities face discrimination in employment and other areas.

The constitution guarantees women equal rights, but gender discrimination is a problem. Only about 10 percent of the seats in Parliament are held by women. Trafficking of women and girls for forced prostitution has become a major problem. However, some law enforcement progress has become evident, and in 2006, the government created a new agency to evaluate antitrafficking efforts and assist victims.

http://www.freedomhouse.org/inc/content/pubs/fiw/inc_country_detail.cfm?year=2008&country=7474&pf

REPUBLICA MOLDOVA

Political Rights Score: 3

Civil Liberties Score: 4

Status: Partly Free

Overview

As Romania entered the European Union in early 2007, Moldovans rushed to apply for Romanian passports and visas, leading to tension between the two countries. Meanwhile, Moldovan president Vladimir Voronin held a series of bilateral meetings with Russian officials on the future of the breakaway Transnistria region. In June, the ruling Communist Party of Moldova lost ground in local elections.

——————————————————————————–

Moldova gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, and free and fair elections were held in 1994. The Communist Party of Moldova (PCRM) took power at the head of a majority coalition in 1998 and won a landslide victory in 2001 on the promise of a return to Soviet-era living standards. Vladimir Voronin was elected president by Parliament.

The only parties that captured seats in the 2005 parliamentary elections were the PCRM, the opposition Democratic Moldova Bloc (BMD), and the right-wing Christian Democratic Popular Party (PPCD). The PCRM took 56 of the 101 seats, and built a broad coalition to obtain the 61 votes needed to reelect Voronin. The only opposition group that did not back him was the Our Moldova Alliance, which had entered Parliament as part of the BMD. Election monitors highlighted a number of flaws during the campaign, including police harassment of the opposition, manipulation of the state media, and abuse of state funds by the PCRM.

The PCRM’s victory was due in large part to high spending on social programs, but it had also gained support by shifting its policy alignments from Russia toward the European Union (EU). Voronin increasingly demanded the withdrawal of Russian troops from Moldova’s separatist region of Transnistria. Tensions mounted in January 2006, when a pricing dispute led Russia to cut off natural gas supplies to Moldova for 16 days. A Russian ban on Moldovan wine and produce imports—a trade that brought in more than $250 million annually for Moldova—further soured the relationship during 2006. In a sign of rapprochement, Russia agreed to lift the restrictions in November that year, but bureaucratic delays prevented the resumption of wine sales until late 2007. Since the bans were imposed, Russia has fallen behind Romania as Moldova’s leading trade partner.

Multilateral talks on Transnistria, which had maintained de facto independence since 1992, broke off in February 2006. The U.S.-based Jamestown Foundation revealed in April 2007 that Voronin had been holding bilateral talks with Russia for more than a year, reportedly yielding a proposal that would reunify Moldova but leave Transnistria with substantial privileges and autonomy. Critics said the proposed deal would bolster Russian influence. The report prompted calls for the resumption of the multilateral talks, which had included Ukraine and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), with the United States and the EU as observers. Ukraine and the EU in late 2005 had stepped up efforts to assist the Moldovan government and isolate Transnistria, launching joint patrols along the Ukraine-Moldova border and enforcing Moldovan customs authority.

As Voronin appeared to repair ties with Russia, his government’s friction with Romania increased. Romania formally joined the EU in January 2007, prompting a surge in Moldovan applications for Romanian passports and visas. An opinion poll released in May found that 38 percent of respondents had applied or planned to apply for Romanian citizenship; many Moldovans had that option under Romanian law, since much of Moldova had been part of Romania prior to World War II. The Moldovan government agreed in January to allow Romania to open two new consulates to handle the load, but it reversed itself in March amid ongoing concerns that Romania was seeking to undermine Moldovan nationhood. In December, Moldova expelled two Romanian diplomats for unclear reasons, and Parliament passed a law barring public servants from holding more than one passport.

Local elections were held in June 2007. The PCRM won with roughly a third of the overall vote, followed by Our Moldova, though both lost ground to smaller parties in comparison with the 2003 results. In Chisinau, the PCRM again lost the mayoral race, despite having the acting mayor as its candidate; the party had failed to capture the post in an election since independence. The winner was Liberal Party member Dorin Chirtoaca, a 28-year-old human rights activist.

Unemployment rates remain high, and the population is in decline due to large-scale emigration and other factors. According to a UN–sponsored report released in June 2007, just 47 percent of the population live in towns and cities. Much of the country’s economic growth in recent years has come from expatriate worker remittances, and up to a quarter of the population may be working abroad.

Political Rights and Civil Liberties

Moldova is an electoral democracy. Voters elect the 101-seat unicameral Parliament by proportional representation for four-year terms. Since a 2000 constitutional reform, Parliament rather than the public has elected the president, whose choice for prime minister must then be approved by Parliament. The presidency, also held for four-year terms, was traditionally an honorary post, but it has taken on significant power under President Vladimir Voronin’s leadership.

The electoral code is generally considered sound, but some regulations favor incumbents. The electoral law in practice discourages the formation of ethnic or regional parties. Roma (Gypsies) are particularly underrepresented. In the 2007 local elections, international monitors reported media bias, intimidation, inconsistent procedures, and other flaws, but said the balloting was generally well administered and offered a genuine choice to voters.

Corruption is a major concern in Moldova, and officials have used anticorruption efforts against political opponents. Despite laws to promote governmental transparency, access to information remains limited. Former defense minister Valeriu Pasat, who was accused of defrauding the Moldovan government in 1997 arms sales, was released by an appeals court in July 2007 after receiving a prison sentence the year before. The prosecution was viewed as politically motivated due to Pasat’s ties to the previous administration. In another case with political overtones, Ivan Burgudji, a politician from the autonomous ethnic Turkish region of Gagauzia, was sentenced in June 2007 to 12 years in prison for embezzling funds while representing his region in Transnistria in 2001–02. Moldova was ranked 111 out of 180 countries surveyed in Transparency International’s 2007 Corruption Perceptions Index.

Print media present a range of opinions, but they are not widely available in rural areas. Only the public service broadcasters have national reach. A new Audiovisual Code, passed in 2006, was praised by press freedom advocates, although some provisions raised concerns, including a vague obligation to ensure “balanced” and “comprehensive” coverage. Prison sentences for libel were abolished in 2004, but journalists often practice self-censorship to avoid crippling fines. The criminal code prohibits the “profanation of national and state symbols” and the defamation of judges and criminal investigators. Despite their legal transformation into public service stations, state-owned broadcasters favored the ruling party in the 2007 local elections. After the Audiovisual Coordinating Council (CCA) warned some outlets to curb electoral bias, four council members were detained by anticorruption investigators in June, creating the appearance of retaliation. In early October, the government faced accusations of political manipulation when the CCA withdrew the Moldovan frequency license of Romania’s public broadcaster, which had been due to expire in 2010. An assortment of press freedom and journalists’ organizations endorsed an appeal of the decision in November. The government does not restrict internet access.

Although the constitution guarantees religious freedom, the government has shown its preferences through the selective enforcement of registration rules. Unregistered groups are not allowed to buy property or obtain construction permits, and many smaller sects, including all Muslim groups, have been denied registration. A law passed in July 2007 banned “abusive proselytism” and denied legal status to groups with fewer than 100 members. It also acknowledged the “special significance and primary role” of the Orthodox Church, although no branch was specified. Earlier that month, President Voronin had indicated his loyalty to the Russian-backed Moldovan Orthodox Church, rather than the Romanian-backed Bessarabian Orthodox Church. Moldovan authorities do not restrict academic freedom, but bribery in the education system remains a problem.

Citizens may participate freely in nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). However, private organizations must register with the state, and some NGOs have complained of government interference. Demonstrations require permits from local authorities. The Supreme Court ruled in February 2007 that the previous year’s ban on a gay rights march in Chisinau had violated freedom of assembly, but the city banned a similar march in April. Authorities exert pressure on unions and their members, and employers violate union rights.

The constitution provides for an independent judiciary. However, there is evidence of bribery and political influence among judicial and law enforcement officials. Some courts are inefficient and unprofessional, and many rulings are never carried out. Laws passed in 2005 on appointments to the Supreme Court and the Superior Court of Magistrates have had some success in strengthening judicial independence. Abuse and ill-treatment in police custody are still widespread and are often used to extract confessions. Prison conditions are exceptionally poor. The government has reportedly handed over suspects for trial in Transnistria, where human rights are not respected. The death penalty was abolished in July 2006.

Members of the Romany community suffer the harshest treatment of the minority groups in Moldova. They face discrimination in housing and employment and are targets of police violence.

Parliament in April 2007 passed a package of economic reforms, including tax cuts and amnesties for black-market assets, that were designed to stimulate investment. However, the International Monetary Fund’s representative in the country warned that such measures would be ineffective without better private-property protection by the judicial system.

Women are underrepresented in public life, though the 21 women elected to Parliament in 2005 marked a substantial increase over previous polls. Moldova remains a major source for women and girls trafficked to other countries for the purpose of forced prostitution. In February 2006, the government adopted the Law on Ensuring Equality for Women and Men, which addresses inequalities in education, employment, and health care.

http://www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=363&year=2008&country=7449