Bucharest’s State Jewish Theatre is a testament to the survival of the Yiddish culture through the Holocaust, Communism and Romania’s uneasy transition to democracy – yet now is threatened with collapse.

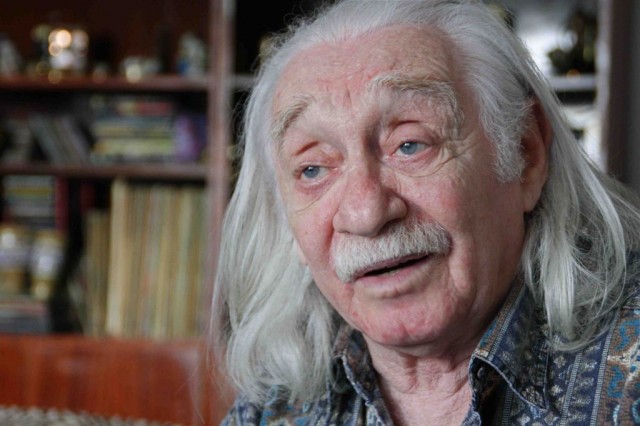

After the Second World War, the theater was a lifeboat for Jewish performers, says Rudi Rosenfeld, actor and holocaust survivor

After the Second World War, the theater was a lifeboat for Jewish performers, says Rudi Rosenfeld, actor and holocaust survivor

In 1980s Romania, under the brutal Communist regime of dictator Nicolae Ceauşecu, Bucharest’s Jewish State Theater staged a play by Woody Allen called ‘Death’.

A humorous allegory of mortality cast as a serial killer in an interwar city, it evoked Eugene Ionesco and the Theater of the Absurd, and touched upon the paranoia and futility of existence that was everyday life during Totalitarianism.

But in late Communist Romania, a theater could not perform a play called ‘Death’.

The censor told the director that if a play was called ‘Death’, the audience would think it was an imperative to wish ‘death’ upon Ceausescu and his wife Elena.

‘Death’ was forbidden under Communism.

Therefore the play needed another title.

At that time, the cinema was screening a revival of the Paul Newman 1950s prizefighter movie – ‘Somebody up there likes me’.

The play’s director, Adrian Lupu, proposed changing the title from ‘Death’ to ‘Somebody down there hates me’.

But the censor was not happy with this title either.

He approached the director and asked him:

“How come you have given this play the title ‘Somebody Down There Hates Me?’” he said.

“What do you have against Bulgarians?”

“Bulgarians?” thought Lupu.

He then realized the censor had taken the title as a literal example of geography.

Because Bulgaria is south of Romania, the name must imply that Bulgarians hold the Romanians in contempt.

This anecdote is rendered to me by Rudi Rosenfeld, a 74 year-old holocaust survivor and Yiddish actor who took the lead role in ‘Death’ and still performs for Bucharest’s Jewish State Theater.

The players staged Woody Allen in winter in a city without heat, where Ceausescu was saving money to pay back international loans by starving and freezing the population.

The audience were dressed in winter coats, while the orchestra would play their instruments wearing gloves.

The theater had to submit the texts for censorship to the Ministry – but these were translated from the Yiddish, which meant some phrases could escape scrutiny.

“The censor’s mentality was: is it against the party? Cut! Does it go with the party? OK, you can stage it!” says Rudi. “But the censorship was made by people who were not very well prepared.”

Rudi recounts how an official from City Hall came to see the one-act play ‘Death’.

“Afterwards, the official came up to me and said: ‘Yeah, I like this show, Rudi, but there is a problem – it made me think.’”

“You can only laugh,” Rudi says now, a frown playing across his face.

Bucharest’s 250-seat Jewish State Theater has survived Fascism, Communism and Romania’s uneasy transition to democracy.

This preserve of Yiddish language and culture remains the most prominent secular monument to the massive contribution Jews have made to Romania over the last two centuries.

But a blizzard in February blew apart over a third of the roof of the 19th Century construction, flooding the stage and threatening the structure of the building, unless urgent renovation work begins.

Jewish State Theater today – a bastion of low level architecture behind tall new blocks and offices

Jewish State Theater today – a bastion of low level architecture behind tall new blocks and offices

The theater began in 1941 as a cultural ghetto for Jewish performers and musicians, because Fascist wartime leader Marshall Ion Antonescu forbade Jews to perform on the Bucharest stage.

The artists collected in this former clinic, built by philanthropist and Doctor Iuliu Barasch, at the heart of the Jewish community in south Bucharest.

However Antonescu banned performances in Yiddish.

At this time the Romanian Army was slaughtering Jews throughout today’s Moldova and Ukraine and the authorities were sanctioning pogroms in Bucharest and the city of Iasi, where Jewish populations were large.

But the actors continued to perform song, drama and comedy to a community on the edge of destruction.

Antonescu held back from ordering a full-scale eradication of Romania’s Jews, especially in the south of the country.

This meant the community remained alive after the dictator was tried by a People’s Tribunal and shot dead in 1946.

In 1948, the Romanian Communist State transformed this product of ethnic cleansing into a celebration of Yiddish culture, turning the building into the Jewish State Theater.

Rosenfeld meets me in his fifth-floor one-bedroom apartment in Bucharest. The rooms are decorated with sketches of costumes for Yiddish performances and a collection of metal scales he has picked up from antique fairs over the years.

Rosenfeld speaks Yiddish and Russian, but today talks in Romanian.

His life mirrors that of the theater – one of survival and a fragile heritage which risks disappearance.

Rosenfeld’s family came from Cernăuţi – a powerful multicultural hub in western Ukraine.

A city developed by Habsburg occupation, in the 1930s it boasted a near-equal mix of Germans, Jews, Ukrainians and Romanians, as well as Poles.

“In the city, everyone got along very well,” says Rosenfeld. “It was an amalgam of languages and people. Entirely atypical compared to what was happening around it.”

However Hitler was planning to annex the Soviet Union with a three-pronged attack through the Baltics, Belarus and Ukraine.

Meanwhile the USSR was also plotting a land-grab and, in 1940, the Red Army annexed Cernăuţi from Romania.

In 1941, Rudi’s mother became pregnant. The day before the Germans undertook the counter-attack, his father went to fight for the Russians.

That summer the Romanian army, as part of the German-led offensive, swept through today’s Ukraine.

Rosenfeld was born in Cernăuţi on 4 August – the moment when Romania’s wartime leader, Marshall Ion Antonescu, ordered the Jews of Cernăuţi into ghettos.

In October, the Romanians deported Rudi, his mother and two thirds of the town’s 50,000 Jews towards Transnistria, part of today’s Moldova.

This was Romania’s ‘killing field’ for Jews, where up to 200,000 Jews and Roma died in unsanitary and murderous conditions.

The mother and son stayed in makeshift barracks in a transit camp in Mogilev-Podolski, until the war was over.

In the camp there were dozens living in one windowless room and he survived due to his mother’s deals on the black market.

“My mother would escape from the camp and go to the peasants to buy milk,” says Rudi, “bring this back and sell it with one more kopek to use this profit to buy milk again.”

At two years and two months old, he became sick with diphtheria – and was close to dying.

“I had to receive injections in my belly and it was hard for her to find a doctor,” he says. “To this day, I do not give blood or have injections because I am afraid. Somewhere in me there is this fear.”

Liberated, he and his mother returned to Cernăuţi, where the Jewish community had vanished.

“You know what family means to me? For very many years I did not know what a cousin or what an aunt is, because all of my relatives died. How did they die, what happened? I don’t know.”

Meanwhile his father joined the Red Army’s march on Berlin, returning home in 1945.

“My father only met me when he came back from the war,” says Rudi.

His father did not want to live with Russians anymore and the family emigrated to Bucharest.

As a skilled carpenter, his father found a job building sets for the Jewish Theater, where his mother worked as a wardrobe assistant. Rudi would push wheelbarrows of materials and carry bricks to help his father build walls and arrange rostra.

“I grew up here,” he says. “I was spending the evenings in the theater. I saw the plays performed at the theater hundreds of times – from rehearsals to the final performances. I was a child of the theater.”

At 12 years, he was singing musical numbers and soon began touring to overflowing halls around the Moldavian region of today’s Romania.

In the 1940s and 1950s Jewish actors would come from Poland and Lithuania to Bucharest.

“After the war, the theater was a lifeboat,” he says.

The theater performed Moliere, Schiller and Balzac in Yiddish, with 45 actors employed and an orchestra of 12, plus 150 backroom staff. There were carpentry, shoemakers and tailor’s departments in the theatre.

“It was like a factory,” says Rosenfeld.

However by the late 1950s the Romanian state was infiltrating the lives of every person.

In 1958, Rudi’s father was chief carpenter for the sets and the technical coordinator. The actors were about to prepare for a large tour.

He went to the director and told him he wanted to surprise the actors each with a suitcase, designed by him, to accommodate makeup, towels and a mirror.

As he started making the suitcases in his workshop, someone reported to the authorities that he was running a private business – an illegal act under Communist law.

He did not use the theater’s wood, but timber he bought himself.

The police did not take that into account and a judge sentenced him and four others to six years in prison.

“Because this is how things were done back then – they would take you, judge you and send you away,” says Rudi.

During the Communist period, Romania facilitated the passage of 100,000s of Jews to Israel. After two and a half years, Rudi’s father left the prison and applied for the right of return to Israel.

But even making such an application was a gamble.

“In the 1950s, if you submitted your documents for Israel, you would be fired from your job,” says Rudi. “About four actors had submitted their documents and they were not allowed to get a job in the theater – instead they worked as laborers building fruit crates.”

In 1964, Rudi and his parents gained the approval to move to Israel. Rudi was at that time married, but was deliberating over whether to leave.

Nearly all the actors who left for Israel could not perform in a country where Hebrew was the national language, which few actors knew how to speak.

“I saw that I would not be able to perform in Israel – nearly all those who left from here as actors were not able to perform there, all others got lost, and then I gave up, I said I would not leave. But soon the Jews left one by one.”

Between 1956 and 1992 the Jewish population in Romania fell from 146,264 to 8,955 – almost all as a result of emigration to Israel.

Meanwhile under Ceausescu in the 1970s and 1980s, Romania destroyed the heart of Jewish Bucharest to make way for giant building projects of wide boulevards and ten-story blocks echoing the totalitarian architecture of Pyongyang.

At that moment, the director of the Jewish Theater, Maia Morgenstern, started acting at the age of 18.

“It was impossible to enter the theater because it was in the middle of a building site,” she says now.

Many of the Jews were relocated by the Communist authorities to Bucharest’s western suburbs.

Therefore the community was hit from two fronts – voluntary emigration and forced displacement.

All that remained was the theater – a bastion of low level architecture in a wasteland behind the tall new blocks, standing like a bright white canine in a mouth of knocked-out teeth.

Only 19 actors were still working at the theater.

To be continued…

Preluat din publicaţia “The Black Sea” (v. aici) cu permisiunea autorului.