Dear Friends,

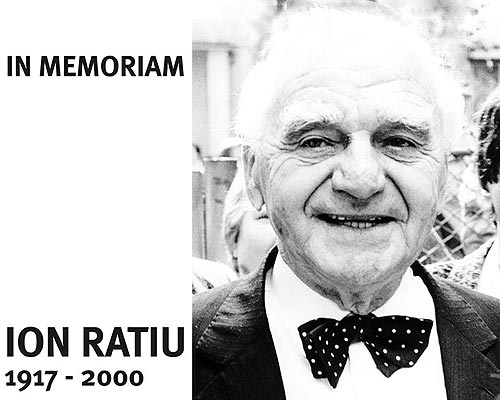

Every year around this date we like to publish our ‘In Memoriam’ in honour of our founder Ion Ratiu. It is a small but for us an important sign of our respect for this great man and Romanian patriot, and also a way of our raising the awareness of his life and work. We like to share this with you.

On Sunday, January 17th, it will be 10 years since Ion Ratiu died. We feel that the best way to pay our respects to him is to celebrate his life’s work rather than to simply commemorate his death – important though that is. We say this especially since we believe that his legacy and his spirit still live and flourish through the activities of the Ratiu Foundation and the numerous projects supported by it.

One thing that people know about Ion Ratiu is that he was completely committed to Romania, working tirelessly on the country’s behalf. The love for his country was a constant from his youth onwards, and it drove him to hard study, both in schools and in private, developing an acute political sense. In order to keep track of his many studies and his work, Ion Ratiu began in the early 1940s to keep organised files and diaries – a habit he continued to his dying day.

We are left at the Ratiu Foundation in London with a huge archive of vast importance for the understanding of the entirety of the Romanian exile from the 1940s to 1990, and also with a wealth of personal papers that help us understand the development of this young man into an assiduous activist for freedom and human rights, forced by the war to stay in Britain.

We are presenting below an excerpt from his diaries – here published for the first time – in which we can catch a glimpse of the 26-year-old Ion Ratiu and his preoccupations. Although living in England for some three years, he was still discovering and deciphering English ways and habits. He imparted his impressions to his diary, just as his ancestor, Ion Codru Dragusanu, put down in letters to friends home his impressions of Victorian England one hundred and three years before him (see the text on our website).

ION RATIU (6 June 1917 – 17January 2000)

Ion Ratiu, the elected leader of the World Union of Free Romanians, based in London, was the most outspoken and consistent voice of opposition to Nicolae Ceausescu. Journalist, broadcaster and author, he was also a successful businessman in shipping and property, while simultaneously assisting in the rescue and support of many who fled Ceausescu’s dictatorship.

After 50 years in exile he returned to his homeland in 1990 to contest the presidency. Although he won a seat in Parliament, and was to serve his country for his last ten years, his failure to win the presidency was a disappointment to many. Even today on Romanian streets, Ion Ratiu is remembered fondly, often referred to as “the best president Romania never had” (read the extended biography on our website).

TRAINS, FOG, AND POLITICS

Pages from Ion Ratiu’s Diary

Friday 29th October 1943

On my return from Salfords, I lived through a unique experience. I boarded the 9.18 from Salfords to Victoria. I was reading “What I have seen in Bessarabia”, a brochure by Em. de Martonne, and I did not notice how time passed. Some time later on, I realised that I should have reached Victoria a long time ago, so I asked my compartment neighbour on the left what the time could have been. It was already 11.30 pm by this time. I should have arrived at Victoria Station at about 10. What could have gone wrong?

It seems my train was slightly delayed in reaching Victoria, just a matter of minutes. It waited for a while on the platform to allow new passengers on board, and then went back towards Brighton at 10.38 pm. It seems I was so engrossed by my reading that I failed to realise this. With a smile that wanted to show indifference, I braved the laughter of my fellow travellers in the compartment, and got off at East Croydon. Disaster was looming for me there! There were no more trains for London. At first, I felt like cursing and whipping my stupidity, but then I recalled Lin-Yu Tang, and I laughed. Oriental philosophy had helped me confront the situation with a light heart, but it was pretty hard for it to transform itself into a means of locomotion. I searched to the right, I searched to the left… Nothing.

No taxis, no buses, no nothing. It was already midnight and I was still looking for a means of transportation. Suddenly I hear somewhere far, in the dense fog, the muffled huff and puff of a train engine. At first I said it was a hallucination: the Brighton to London line is electrified! But the noise persisted. I ran to the station manager and I asked him what it was: “It’s the goods train that brings vegetables, eggs and other rationed goodies to London’s restaurants”. I didn’t wait for another confirmation of the train’s existence and I ran straight to the platform. The train had just stopped in the station.

“Are you going to London?”

“Yes, we are.”

“Could you be so kind as to take me on board? There is no other possibility for me to get home tonight.”

The driver looked at me, as if weighing me up, and after a short pause he said “Get on board!”

I entered a carriage which was filled on one side with tomatoes, cabbages, and fruit, while the other half of it serving as the train guards’ cabin. There were two guards. I said good evening, and according to English custom, I adopted a dignified silence. Several minutes passed without any other words being exchanged.

“It’s a bit thick, isn’t it?” These words have been spoken by one of the guards, a man of about 60.

He was evidently talking about the fog. This is something everybody needs to know: in England, any conversation starts with an observation about the weather. For a foreigner visiting the country, this curious custom seems absurd and is generally attributed to some annoying politeness. But after two or three years of continued living in England, our foreigner realizes he will commit the same sin. And this is where the true explanation comes to light. The weather in England is very changeable and generally dominated by a calm and monotonous greyness. When it’s sunny, the light and heat are not too intense; when it’s cloudy and raining, the clouds are not too dark, nor too threatening. When it’s foggy, it’s just enough fog to make the trains run late and to change the colour of your shirt collar from white to grey. Everything tends towards greyness. The colour is uninteresting, opaque, boring even, but full of unsuspected depths. Thus, whenever something that is far from the norm comes up, people feel the need to say it. It’s a piece of news like any other, news that requires comments.

Once the silence was broken, I was ready to get talking to the guards. However, I did it with much caution, not wanting to betray my quality of being non-English, which would have led to a series of boring explanations [for my presence there]. That is why I let them speak first. One thing leading to another, we started talking about the political situation – the leitmotif of any discussion during wartime.

My interlocutor was a passionate supporter of Russia. He was very critical of the capitalist regime. Sometimes his critique was profound and healthy; at other times it was characteristic of the demagogy of Communist slogans. This made me fire up, so I found myself – to my great surprise – defending the present political regime, but also noting the need to bring important reforms. We talked like this all the way to London, him bringing his arguments, and me bringing mine.

The train was running lazily through the night. The lights in our carriage were dimmed, and the fog was seeping inside, bringing its smoky smell, evocative of the sweat of one’s face during daily work. The two guards were not hostile to me, but they showed they considered me a member of the class that looks to exploit them. The atmosphere of clandestine political meeting was thus complete.

Step by step, I became more passionate myself. I talked about the tradition of freedom in our country (meaning England; I was talking as if I were an Englishman), about the good fortune of enjoying continual peace (on this island) for some thousand years. I talked about our democracy which, for better or worse, establishes an entire series of freedoms such as not many countries have had the occasion to experience. I also talked to them about the need to achieve economic equality and that “freedom from want” President Roosevelt was talking about. I talked about cooperation between the members of the community, about the unity represented by the state, and about the extraordinary possibilities for development if all members of the community would work toward the same goals.

I finished by telling them that they will have their Beveridge (1), and Uthwatt (2) and Workmen’s compensation, but only if they will be united, and will persist in gaining these rights. The extreme conservative group will have to give way because of popular pressure, especially given that a great part of the young conservatives wanted themselves to bring changes.

“It’s not mandatory to throw away everything we have built during the centuries, everything that is good and has proved able to live through the hardships of a war such as the present one, but we shall have to bring a series of modifications. The forces that tend towards a new political orientation are growing. All that is left to do is for us to be strong, and what the working class wants will be realised for the benefit of the entire community.”

We have reached London. My interlocutor reinforced my words: “We don’t want a revolution. We want our rights, and we are going to demand our rights”. We shook hands with sincerity and I made to leave. The fog outside was very thick.

“I’ll walk you to the exit, Sir” said the other train guard. At the iron gates of Victoria Station that he opened for me, he shook my hand and told me “I was happy to hear you talk, Sir”.

This day has not been lost in vain!

* * * * * * * * * *

NOTES:

(1) William Henry Beveridge (1879-1963): British economist and social reformer. Perhaps best known for his 1942 report Social Insurance and Allied Services (known as the Beveridge Report) which served as the basis for the post-World War II Welfare State put in place by the Labour government.

(2) Augustus Uthwatt (1879-1949): British judge. Author of the Utwhatt report on compensation and betterment, and land utilisation.

The Ratiu Foundation

Manchester Square

18 Fitzhardinge Street

London W1H 6EQ

Tel. +44 20 7486 0295 • mail@ratiufamilyfoundation.com

More details on www.ratiufamilyfoundation.com

DEAR SIR,

I ENJOYED VERY MUCH YOUR SO SENSITIVE PRESENTATION,AND A LITTLE MORE THAN THAT,IF YOU ALLOW ME TO SAY SO,THE FOGY NIGHT STORY,WRITTEN WITH A HIGH SENSE OF EXCELENT HUMOR.

THANK YOU VERY MUCH.

ITZHAK BAREKET.

am văzut un singur urmaş al lui Raţiu, Victor Ciorbea, dar nea Emil cel incapabil l-a terminat, împreună cu veşnicul Iago cel >Băsescian